Currently, retailers in the US are facing $45 billion of excess inventory, up 26% from 2021. The good news is that the supply chain and finance teams responsible for clearing inventory have options. These include predictive analytics and tools to reduce inventory from becoming SLOB - slow-moving, excess, and obsolete inventory like Syrup Tech.

If teams still have any leftover inventory then can list on auction marketplaces like Liquidation.com, bstock, have returns liquidated by bulq, or run private direct sales on inturn or ghost. Despite, all of these tech-enabled options, with retailers having their own clearance sales, and donation opportunities -> the top US retailers still have $45 billion of excess inventory.

In this article, we will explain how retailers and manufacturers alike face over 20+ steps and plenty of decisions to make in their attempts to find the right way to liquidate their SLOB.

ERP

Where SLOB hangs out.. until it dies

ERP systems such as those offered by Oracle offer finance teams the ability to manage inventory transactions and set pricing for inventory write-offs. Netsuite explains that one way to measure SLOB is to keep track of how long items have been sitting in a warehouse called 'days at hand.'

As the finance team has to oversee pricing and transactions for GAAP, it's the supply chain team then that must coordinate with Distribution Centers (or Warehouses) and run cycle counts to confirm inventory quantities.

Warehouse management systems (WMS) and inventory management systems (IMS) are concerned with tracking batches and product attributes. Batches refer to when certain inventory was created, and SLED or shelf life expiry date refers to the date the inventory is considered expired by the manufacturer.

By practicing a first in, first out (FIFO) practice of managing inventory, supply chain teams hope to move inventory out of their respective warehouses before items need to be accounted for by finance. Product data such as product attributes help also segment inventory so items are easier to clear in bulk if needed.

At this point, all is well... until it isn't.

This is because ERP systems were designed to be worked on with data silos which was a way to prevent the wrong business unit from getting access to sensitive data sets. So instead of collaborating proactively, oftentimes, SLOB has to be handled reactively.

This means that supply chain teams don't have valuable historical data to know the best channel to liquidate based on aging and price, and finance teams can't track which batches ultimately get sold, which might otherwise help in coming up with more granular pricing and discount strategy to save time.

Cost Recovery vs Speed

To combat SLOB, each team has their own focus, often times at odds with one another

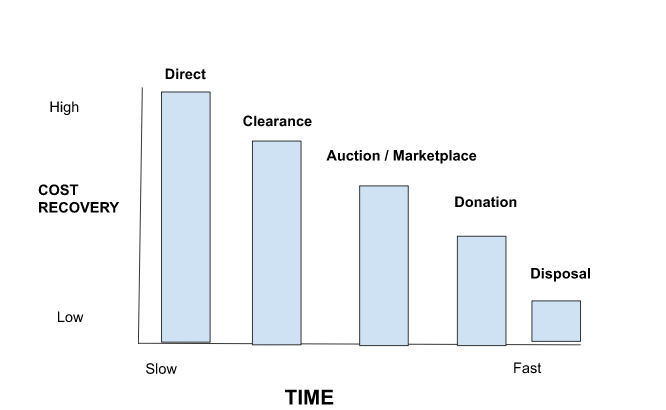

Cost recovery requires finance teams to try to maximize the amount of capital that can be returned that was originally invested in the creation of the inventory.

The challenge is how to clear warehouse space, where SLOB is preventing more profitable inventory to be processed when the best cost recovery options are the. slowest

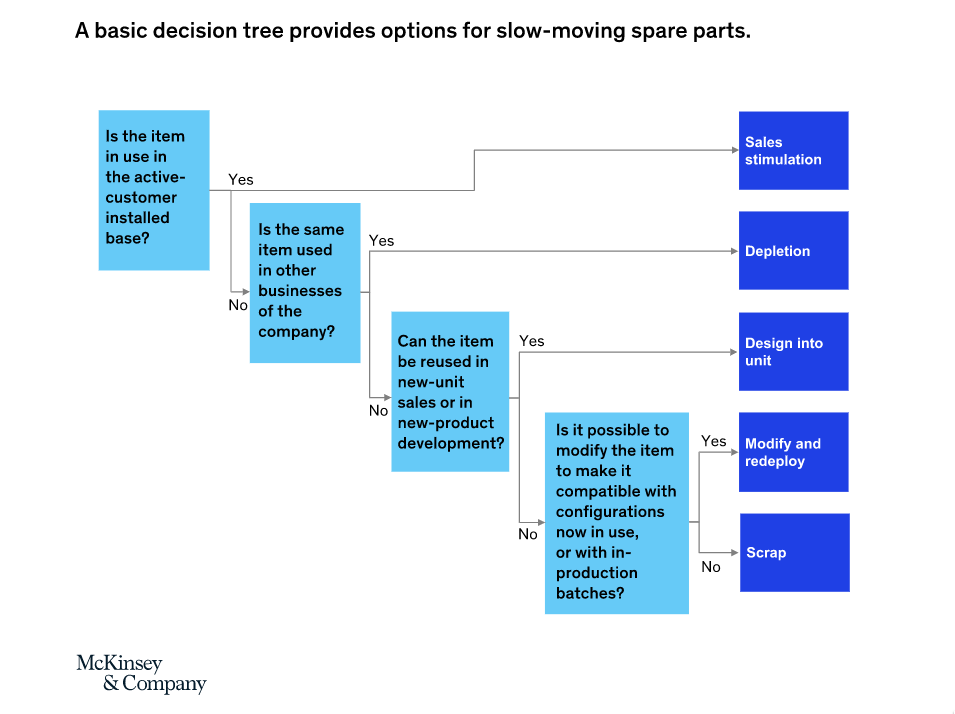

This is why most manufacturers and many retailers have mastered the art of having multiple channels. Take, for example, the below automotive part. There isn't a quick-win solution. Instead, multiple decisions are needed to be made by humans, which at scale leads to slower liquidation time and lower cost recovery- something no one wants.

When fast-moving consumer goods companies (FMCGs) invest in having more than one warehouse, it further adds complexity to the WMS and the teams managing them. Oftentimes, a 'hidden' SLOB happens when inventory from one warehouse or DC moves to another. It's also easy to blame no one to take ownership. Thus, the problems keep reoccurring.

WMS

Where SLOB lives on

A good warehouse management system allows supply chain teams visibility over current market demands by monitoring the inbound/outbound requests from their distribution centers. This includes basic capabilities such as tracking items by barcodes and documenting product conditions at a batch level with photos taken by the staff.

It might seem surprising, but SLOB often isn't separated on a physical level - that work happens with the finance folks and at the ERP level- meaning quality control and assurance becomes vital in verifying what is and isn't actually SLOB when they cross-check or run cycle counts.

In liquidation sales, buyers familiar with these processes (as many have their own warehouses and WMS) will usually attempt to de-risk their inventory purchase of SLOB by requiring additional assurances or checks.

The first check happens for pre-order/payment. This is usually some sort of visual inspection, done in person by the buyer's appointed agent or staff, or if cross border could be in the form of a product sample shipped by the seller or the seller conducting their own inspection in the form of documented photo and videos with timestamps. Clearly the first time a buyer purchases, they will have more reservations as opposed to repeating customers.

The second check usually happens upon the order confirmation. This is an additional supply chain QA check to verify the condition and quantity haven't changed. Now, why is that needed if the items were previously checked and confirmed?

This happens because the WMS was not designed for liquidation sales, which doesn't have a single destination or channel. Without telling the supply chain teams using the WMS, there could have been adding fresh stock sales where kitting/bundling happened and some SLOB was cross-sold.

It would have been an approved donation, or even some grey market or illegal reselling could have happened from local warehouse staff looking to earn extra income. A number of reasons could have happened, none of which are documented or even easily traceable to who requested and who the receiving party is.

So one way to mitigate against slob remaining inside of a WMS and resulting warehouses connected is to enable multi-channel liquidation sales.

Multi-channel Liquidation

Choosing the right channel at the right time... but how to decide?

No one would say being a referee in a professional sports league is an easy job. You have to often times make instant decisions and can't consult a rule book or ask for a second opinion. One team says there is a foul, and the other doesn't. Who is right?

Both want the same thing- the right decision that is going to favor them and advance them to victory. The wrong decision and you ruin the integrity of the outcome. The right decision and half of the players and fans still think you are wrong.

To improve some of these outcomes, technology-assisted video reviews have been implemented. This also means that the scoring or rating of these outcomes can be analyzed and studied by future referees, who in turn get better at making the correct decision as their experience grows from data review and work experience.

With liquidation, there are essentially two teams who should be working together but because technology hasn't been focused on liquidation, a virtual tug-of-war happens. When there isn't a clear winner, a liquidation referee of sorts emerges.

On one hand, finance wants the highest recovery rate possible for the SLOB already written off. If the cost of goods sold (COGs) or total landed cost is 10, then getting 5 might be considered a 'win' on their scorecard for their team.

At the same time, we have to consider the situation on the ground, the SLOB in the WMS, and the actual warehouse managed by the supply chain team. a 50% recovery rate goal is something great in principle that may or may not happen instantly. It could take days, weeks, or even months to fully clear. In the meantime, this SLOB is sitting hidden in their daily workflows and potentially clogging up more profitable inventory from being sold.

So who wins... recovery or time?

To answer that question, our liquidation referee often has to make non-data decisions. If the referee appeases the supply chain team, then it means ignoring the desired recovery rates set by the finance just to clear items asap. This could be a disposal or donation opportunity.

The supply chain team would feel validated in the right decision since they moved more unsellable items out of their warehouse. At the same time, the finance team might be frustrated at this decision knowing they lost out on recovery potential.

Thus, to make up our referee could make a decision to only liquidate to large bulk buyers and to consumers via direct sales or clearance channels. This might mean additional time to then manage the entire sales and order process, to mention the logistics and additional work strain on the supply chain to enable these channels which may or may not be part of their day-to-day.

The rules may say that once a product reaches 6 months of shelf life, reduce the price by 10% for a total discount of 60%. That certainly sounds like a plan both sides of the tug-of-war could get behind.

That's where third-party marketplaces and liquidation vendors come into play to split the difference between 100% DIY recovery options that are great for finance but poor for supply chain teams or disposal or donation with the opposite result. The challenge is that these channels are not connected to the various data inputs and have very low visibility of the company's priorities of recovery rates vs time - in sense promising both.

The referees here are not even full-time, like the professional sports ones. They are often executives or from adjacent supply chain or finance functions such as regional managers. These people are not to be blamed, but rather admired for being brave to make incredibly hard decisions with little data to rely on.

Control

the decision of recovery vs time often comes down to protection of brand and price

As far as making the important tie-breaking decision of what to optimize for when it comes to liquidation desires vs protecting the image of the brand including contractual obligations on price and distribution.

Pricing considerations are important for high-margin products such as luxury goods where a certain price is required and expected by the brand and its stakeholders. In some situations, this consideration has led to brands like Burberry throwing away products for fear of price erosion on unauthorized resale channels.

Control over channels typically is linked to ownership of the rights to resale the brand. If the brand owner is the principal, they have to ensure they are not infringing on partner companies which could be related companies in other territories or franchisees or distribution partners.

So control of price and distribution channels are both of high value to brand owners. Offline ways of liquidating inventory reinforce the challenges in enabling control because traceability and transparency of data are lacking.